COVID-19 has been wreaking havoc everywhere. Global stock markets, like the global population, have not been immune. Because the outbreak started in China, we thought it would be a good time to take a fresh look at investing in emerging markets. Who should invest there, and to what degree? What are the risks and potential rewards?

Investing anywhere involves risk, as we’re seeing up close right now. But the level of risk varies, as do the types of risk. We don’t generally worry about a government coup in the United States, for example. We also assume that our government’s debt, as vast as it is, will be backed up by the U.S. government no matter what. A default seems almost unthinkable.

That’s one reason why that debt doesn’t pay much in interest. It’s low risk. Emerging market debt is a different story. A lot of it is high-interest, low-rated debt due to risks unique to these markets. Political instability is one of these risks. Currency crises are another big one. Natural disasters can occur just about anywhere, but many emerging-markets countries are often more prone to floods, typhoons, earthquakes, drought, and much else. So many risks that we in the United States don’t even think about are common occurrences around the world.

In exchange for dealing with that additional risk, however, you might enjoy some outsize returns. These are, after all, some fast-growing places. Consumers are gradually bringing home more disposable income; population growth is strong; stability might even become more of the norm over time. For all of those things, you can be rewarded handsomely.

You have to have a strong stomach, though. Take a look at the annual returns of any emerging-market, country-specific ETF and see for yourself. Double-digit annual returns, both positive and negative, are common. But over longer periods, you can expect a lot more on the positive side than the negative side.

All Aboard The Volatility Express

Once you’re onboard with the idea of putting a portion of your money to work overseas, the question then becomes how much.

Generally speaking, those earlier in their working career should commit more of their investment contributions (via 401(k)s and IRAs) to riskier asset classes such as emerging markets. Foreign markets will crash and burn on occasion, but over time, given their population demographics and increasing middle-class consumer numbers, many of those markets should grow faster than our own.

The key — and this is also where it helps to be earlier in your investing years — is to keep investing through thick and thin. That is, just as is the case domestically, you can’t try to time the markets. If you basically set and forget your contributions so that you’re buying at the bottom, the top, and all points in between, you’ll average in at good prices and should do well.

The later you are in your working years, the less you’ll probably want to be invested in volatile markets. But that is a call you’ll have to make. Watching our domestic bull market collapse reminds us that diversification — across asset classes as well as countries — is good practice, even if, in this particular case, there appears to be nowhere to hide from this worldwide calamity.

Extreme Under-diversification

Consider this highly unlikely scenario: a 55-year-old couple who invests their entire investment portfolio in emerging markets. Their thinking is that they would like to retire at around age 68, but don’t think they have the investment firepower to make that happen. In short, they want to juice their returns between now and retirement. They have about a million dollars’ worth of assets and intend to spend $65,000 annually after retiring.

They plan to hold off until 70 to take Social Security. But with the way the markets have been roiled, they’re starting to wonder if they’ll be able to wait that long.

When they run their emerging-markets-laden plan through the WealthTrace financial planning application, things look pretty rosy at first. In 13 years, their portfolio could be worth nearly $5 million in today’s dollars. Sources of income (the bars in the graph below) cover expenses (the line with the circles) so comfortably, they start talking about retiring earlier.

But hold the phone. Inherent in that upward trend are few assumptions, one of which is not to be relied upon with an asset class as volatile as this one: that their portfolio will enjoy the same returns every year.

Remember what we said earlier: “Double-digit annual returns, both positive and negative, are common.” There will be zigging, there will be zagging. Estimates of straight-line returns have their place but are most useful (1) over longer periods of time, and (2) when a portfolio’s asset classes are more conservative in nature. Average historical returns on asset classes are less useful the shorter your time frame is, and this time frame (about 13 years) is relatively short.

So we need to use another tool for this job, and that tool is Monte Carlo modeling. Briefly, Monte Carlo allows you to have a look at a lot of possible outcomes based on historical asset class performance, and how asset classes interact and are correlated with one another.

With a portfolio of 100% emerging-markets stocks, correlation doesn’t matter. But volatility sure does:

What on earth is happening here? The dial tells us the plan only has a 28% chance of succeeding — a far cry from having $5 million in assets at the end of their lives. The inherent volatility of emerging markets explains the graph on the left with the grey lines. If you look closely, you can see there’s a one-in-a-thousand chance that they die with $80 million! But there’s a much larger chance (72%) that they’ll run out of money before then. Indeed, it’s not shown here, but WealthTrace calculates that there’s a 25% chance that they’ll run out of money at age 64. We don’t like odds like that, and we’re sure our hypothetical couple wouldn’t either.

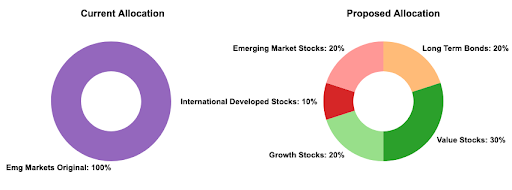

If we take the portfolio and diversify it, giving our couple a more reasonable mix of assets, things look a lot better on a probability perspective — though to be sure the plan is going to need some additional tweaking to get the proposed allocation’s probability number higher:

Stretches of market turmoil are tough to stomach, but they can also be a time to reassess. Do assumptions you held a few months ago still hold? Investors in United States equities almost could do no wrong over the past decade or so, but things have obviously changed. As always, though, investing prudently still depends on your time frame, risk tolerance, and goals.

Comments